Who will be the “winner” during the recession in the photovoltaic manufacturing industry?

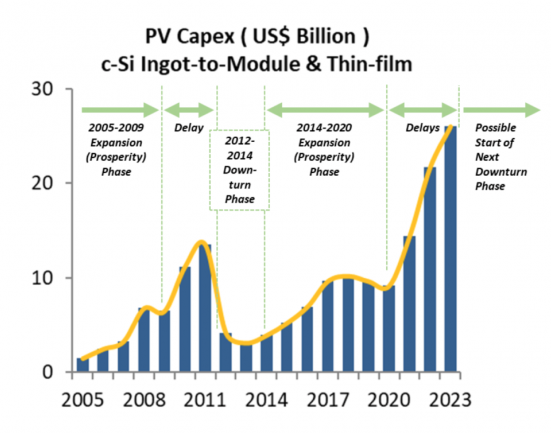

If there is a manufacturing recession in 2024, capital expenditures (in the crystalline silicon sector, especially ingots, wafers, cells, and modules) may be a leading indicator of this recession. Capital expenditures are often directly linked to periods of economic downturn, and the PV industry has seen this happen before.

First, before 2009, the photovoltaic industry was mainly in the growth stage, and before that, the industry had been a cottage industry that emerged from a research base. Capital spending is almost entirely aimed at increasing production levels among a small group of Western companies. Polysilicon is borrowed from the semiconductor industry. There is no overcapacity, and although manufacturing profit margins are not amazing, there is a certain degree of order behind investment and growing market demand.

In 2009, the entire industry was about to enter a recession, or at least see the flattening effect of crystalline silicon capital expenditures. At the time, surging capital spending on thin-film technologies such as amorphous silicon (a-Si) and copper indium gallium selenide (CIS/CIGS), which had been seen as potential options for mainstream silicon-based manufacturing technologies, somewhat delayed the rise to decline. Transition.

The artificial peak in capital expenditures in 2010-2011 was mainly driven by equipment suppliers in the flat panel display space (such as Applied Materials, Oerlikon, and ULVAC), which sold amorphous silicon turnkey production lines to newly established companies. These efforts fell short, and the spike in capital spending during this period is the legacy.

Eventually, as outlined earlier in this article, the recession did begin. The downturn in 2012-2013; the upswing in 2014-2020; and the downturn delayed until 2023.

Capital expenditures for the period 2020-2023 are out of sync from any perspective and are on a completely unsustainable trajectory. If this article only showed capex, alarm bells would be ringing for 2024. By then, capital expenditures will experience negative growth.

However, forecasting capital expenditures is very difficult. Ultimately, we can only track the movement of funds in real-time. Today, since most equipment orders fall on Chinese companies, it is impossible to understand the indicator between orders and shipments. During the first industry recession, the orders-to-shipments ratio was the ultimate (capex-driven) leading indicator that foreshadowed a difficult period for manufacturing from 2012 to 2014.

This was tracked because Western listed equipment suppliers, which were the mainstays of PV manufacturing at the time, were heavily audited for their (actual) order volumes (and backlog). Ten years ago it was possible to analyze orders and shipment ratios, but today it is no longer possible.

Broadly speaking, PV manufacturers do not build, operate, or own solar projects. Some companies will be involved in the final development and initial construction phases, but even these companies will transition to long-term asset owners quickly or when cash is needed. Therefore, we can rule out the possibility that PV manufacturers engage in industry-related activities and thereby obtain secondary benefits when module prices (and prices across the value chain) are depressed.

Of course, the winners are those who buy the components, at least in the short term. Still, buying components, even at low prices, can be problematic because the supplier's financial health is at greater risk than normal. How much is a 25-year warranty worth? Will quality be compromised because everyone wants to reduce costs?

What are the additional risks if half of the parts used in an assembly come from newer companies that are currently losing money and whose long-term survival prospects are in doubt? There are many more questions like this. So, yes, low component prices are great, but for anyone in the industry, the risk of a manufacturing bust far outweighs the opportunity.

Potential winners also include component suppliers owned by large corporations with deep pockets. These companies believe that owning a photovoltaic manufacturing business has enough strategic value to effectively provide financial support for their photovoltaic manufacturing vision (more than in good times). Truth be told, there are very few of these companies, and they are usually not among the top ten component suppliers by volume. When it comes to product pricing and market share, the top ten component suppliers call the shots for everyone.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity presented by the decline of PV manufacturing in 2024 and 2025 (mostly China-centric) is that the entire Western PV stakeholder group takes this issue seriously; for start-ups, technology leaders and manufacturing ecosystems Support the system’s stakeholders and give them a “moon shot” directive to achieve success by 2026.

Regardless, get ready for a bumpy 2024. Let's wait and see which companies will be the first to reset their spending targets and market growth vision.